Twentieth century Land Rovers are tactile; you push a button, turn a knob, push a lever, and flick a switch. In turn you receive feedback — the button resists, the knob twists, the lever slots in place, the switch clicks. When you accelerate you feel resistance at the pedal and as a result you hear the exhaust. Road feel, wind noise, body yaw and pitch comprise key parts of the driving experience. My IIA’s exemplify tactile; even Gilroy, my ’97 Discovery I, lets me know what’s functioning (or not) inside or outside the car. I can keep my eyes on the road as my tactile senses remain active during the drive.

Twenty-first century Land Rovers fulfill different expectations. When we text we use our thumbs, so many controls migrated to the steering wheel where our thumbs control functions. As an alternative, our fingers push a visual circle or box on a center screen to initiate an action. Those controls inside the Land Rover mimic the tactile experiences of our smartphone age. We rely on an aural or visual confirmation of an action, not a tactile one.

Contemporary drivers — backed by government mandates — expect that vehicles anticipate driving issues and either alert or take control of certain required actions. Electronic wizardry does make new Land Rovers extraordinarily capable in all driving situations, off-road and on-road, but reduces driver input and feedback such that one might not realize how lucky they were to get through an obstacle or swerve in an emergency. There’s an old saw that notes four-wheel drive increases the degree to which you get stuck, and even the latest technology can’t overcome the laws of physics.

Back in mid-January, when travel seemed routine, Land Rover made it possible for me to attend the 4XFAR Festival. I drove the QE I (’66 Series IIA 88” SW) 80 miles to the nearest airport and began my various connecting flights to Los Angeles. There, Land Rover enabled me to enter the 21st century vehicular world. To paraphrase Sam Cooke, a change has already come.

To get me to Palm Springs for the Festival, Land Rover spoiled me rotten with a Range Rover Velar SVAutobiography for the drive from LAX. Imagine going from a 77 hp 4-cylinder engine to a 550 hp supercharged V8, from seat squabs to ergonomic bucket seats, “elephant hide” to sumptuous leather, from leaf springs front and rear to double wishbone front suspension and multi-link rear suspension.

I had visions of releasing the Hollywood in me until the Velar’s navigation system guided me into miserable LA traffic [at 3:30 in the afternoon!] onto “the 405”. [Is that Hollywood enough?]The route should have liberated me to test out the Velar’s silky drive capabilities; instead, I joined hundreds of thousands of commuters staring at mall traffic in Torrance, Garden Grove and especially, Riverside. The 128-mile drive should have taken two and half hours. Four hours later, I arrived in Palm Springs. On the other hand, I’ve never been so comfortable sitting in traffic.

Land Rover must have seen the potential for grand larceny as they took the keys away from me at the hotel. The next morning they graced me with a Discovery 5 diesel to drive myself back and forth to the festival grounds in nearby Indio. My partner for the event, rallyist Deborah Njam, fought valiantly to decipher the inaccurate navigation directions to the entrance of the Empire Grand Oasis site; fortunately, she had attended Coachella Festivals in the past and could suss out a route. Her choice of a route took us over dirt trails that let us enjoy the Discovery’s off-road suspension capabilities.

At the Festival’s end, Land Rover’s terrific travel team urged me to leave Palm Springs by 5:30 am to make my late-morning flight. Out came a new Discovery Sport for me to drive, resplendent in its upgraded interior. I put it in Sport Mode and took off on what turned out to be a relatively traffic-free drive; it seemed to take longer to navigate around LAX and return the Discovery than make the drive. I’m a fan of the Discovery Sport’s small footprint and the interior enhancements made it an even more endearing drive.

By the time I’d returned to Maine, I thought I had my fill of 21st century Land Rovers — but no. Gilroy had been sitting in a hotel parking lot for a few days in the frigid cold and snow of mid-January. When I arrived from the airport that night, I went to swap out my warm weather clothing for winter gear. Unlocking the doors with a key did not return the usual “beep” and flashing sidelights. Opening the door did not enrage the dome lights, nor did turning the ignition to “on” produce any dash lights. My multimeter indicated the battery held 2.5 volts. The front desk greeter acknowledged they had moved the car after a snowstorm. A check of the dome light switch told me they had left the light on throughout my stay.

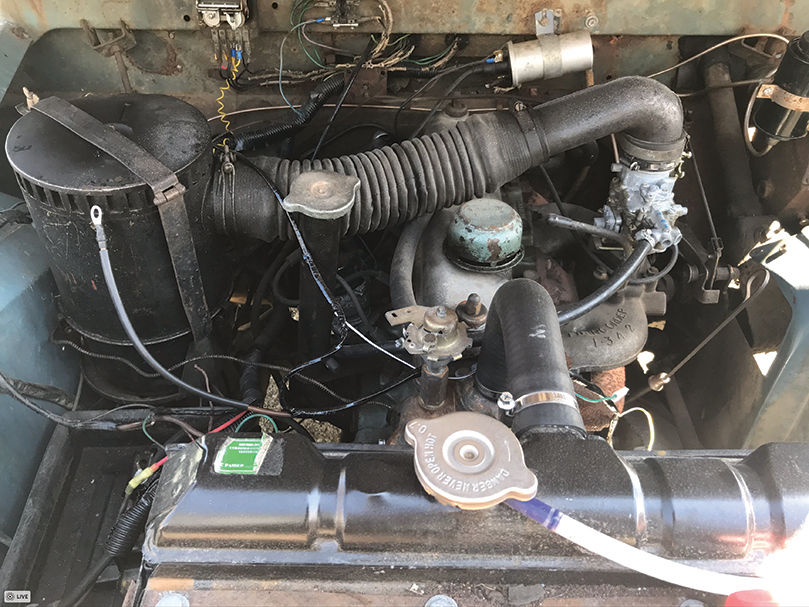

I gave the Discovery a jump start the next morning and left it running for 10 minutes or so while I checked out of the hotel. I slid into the driver’s seat to find the temperature gauge pegged on “H”. Opening the hood revealed a fan actively turning and coolant spewing out of a crack in the plastic reservoir. That forced a tow to the dealership and a rental Discovery 5 to get me home. I would enjoy it for a week while waiting for the diagnostics on Gilroy. Fortunately, the head gasket held and the only repair required was for a new reservoir. Justin Alley, the Parts Manager at Land Rover Scarborough noted, “They all do that,” but I still preferred my 20th-century ride.

In Grade 6, I took a standardized exam intended to signal a potential career path. One section tested my ability to see relationships between moving parts; I did so poorly that my teacher said to me, “I’m surprised you can open a doorknob.” In decades of columns and articles I’ve laid bare the predictive accuracy of this test. My reality remains that I’m less of a mechanic and more of what we call in Maine a “dubber.”

When I drove Rickman the Virginian, my ’67 109” SW, home from Virginia to Maine [see Winter 2020 issue -ed.], I managed to get one day of (nearly) carefree driving before encountering a problem. When I turned it off at a motel in Connecticut, the ignition light remained on. Jiggling wires at the alternator accomplished nothing, so I pulled off the negative battery cable. When I reinstalled it the next morning, the light remained off, illuminated when the key was turned to on, and remained off after start up. Using a multimeter I checked that the alternator was working and continued my drive back to Maine.

Even worse, despite my staring at a jiggling of wires, the problem morphed into a full battery drain when the IIA sat for any length of time. While I could remove the cable after each drive, dubber-style, I chose to affect a repair. Changing out the clip at the alternator accomplished nothing, so next came a replacement alternator, which led to the same outcome. That made me wonder about the 53-year-old wiring with its non-stock appendages.

I studied schematic diagrams carefully and tried to understand the relationship of the electrical system. Quite certain I had it right, I hooked up the wiring again and started the 109”. My first hint that all was not correct came when smoke rose from the positive terminal wires at the battery. Key off, cables off and I could put away the fire extinguisher. Perhaps James Parker in The Atlantic had me in mind when he wrote, “So here’s to being fallible… tolerance for error is a must. Even Solomon blew a call now and then.”

Last February, I filled the 12-gallon tanks in the Series Land Rovers. In early March, I filled the 23-gallon tank in the Discovery. As of May, I’ve not added gas to any of them — that’s how little I’ve driven during this pandemic. Clearly, I’ve not spent much time behind a steering wheel.

If you’ve not been able to spend time on your Land Rover, perhaps you might tackle the 2,573-piece LEGO Technic Defender. Matt Browne, Berwick, ME, of Overland Engineering, received his kit last Christmas. He marveled at the intricacy of every system, such as the rear suspension. Dartmouth College professor Nathaniel Dimony bought one to give his 9-year-old daughter Eleanor something to do during their quarantine. Eleanor told me, “It took us about two weeks to assemble it, in between my classes at home. It was really complicated, but really cool!” Nathaniel noted, “It’s quite complex — you even assemble the gearbox and transfer case. I learned a lot about the innards of my ’91 Defender 110!”

I’d buy one if it could teach me how to install a 109” engine harness.